Another enjoyable Wimbledon Tennis Championship draws to a close. Each year, as a racquet-ball widower, I draw upon the alternative entertainment on offer at the Curzon cinema – and by digital extension, Curzon Home Cinema – to help me through the fortnight of tennis. I’ve already reviewed The Midwife and A Man Called Ove; here’s the second rally, effected over two days. (As an embargo prevents me from reviewing Dunkirk until tomorrow, I feel I should honour the smaller films on offer.)

The “biggest” of the five films I’ve chalked up is The Beguiled, in the sense that it was directed by Sofia Coppola, who picked up an award at Cannes for the painstaking trouble she went to in remaking an ancient Clint Eastwood film for the Millennials. It’s certainly not the longest of the five pictures that entertained me over the weekend: at 94 minutes, it’s nine minutes shorter than Don Siegel’s 1971 version, but then, Coppola has chosen to excise the black slave character Hallie (Mae Mercer) for fear – I have assumed – of muddying the waters of the story for white liberal viewers. It really is gorgeous to look at. Coppola’s films tend to be. Shot in Louisiana, for Virginia (It was set in Mississippi in the original), it’s a fecund setting, all shafts of light and trailing fronds, a wall of natural beauty between the virginal/celibate, starched female inhabitants of the Farnsworth Seminary for Young Ladies (two adult tutors, five remaining young ladies) and the outside world ie. the grim reality of the American Civil War, fetchingly hinted at by photogenic wisps of smoke in the far distance and tiny thrums of gunpowder igniting. Colin Farrell plays Clint’s Corporal John McBurney, the injured Union soldier taken in by the seminary to convalesce and to ruin the hormonal balance of the plantation house.

I don’t object to beauty for its own sake. Film is a visual medium, after all. But The Beguiled lacks freight. It is almost weightless. Even when Farrell’s sap rises, it’s as glimpsed and hinted-at as the plumes of war. He has one outburst – the one with the pet turtle if you saw Clint in 1971 – but even that’s cauterised. His fate will come as no surprise to anyone who saw the original film on TV, as I did as a kid , or who saw this remake’s trailer, which gives the whole game away. It’s an oddly neutered version of the original film. When Nicole Kidman’s headmistress washes the war-filthy body of an unconscious Farrell (something the slave did in the first version), he looks like he’s already been pre-washed. When the ladies do what it’s clear they’re going to from the trailer, it’s all off-screen. A tale of violent coming-of-age in a violent era it may be, but the violence is not even worth mentioning on the BBFC classification card (only “infrequent strong sex” – if you insist!) It reminded me of Coppola’s delectably moody debut, The Virgin Suicides (which shares Kirsten Dunst with The Beguiled, now all grown up) – but that really was beguiling. It’s like she’s moved from art to home decorating.

Get Out (released earlier in the year and out on DVD next week) is the polar opposite of The Beguiled in terms of squeamishness around race. Written and directed by feature debutant Jordan Peele – half of an acclaimed sketch double-act Key & Peele, yet to be exported here – this is a horror film about race. It comes on like a laser-guided post-Girls satire on the terror of white liberals around black people, with Chris (British export Daniel Kaluuya), the “black boyfriend” of Rose (Allison Williams), who’s taken to meet the rich parents in their cloistered suburban enclave, where the only black faces belong to “servants”, about whom Mom (Catherine Keener) and Dad (Bradley Whitford) are wracked with progressive guilt. (Rose tells Chris she never told them he was black, and why, as a colourblind liberal, would she?) From the get-go, Get Out is different. On first inspection, though drawn as figures of fun, the parents aren’t racist. The subservience of their black maid, and the compliance of their black groundskeeper, give cause for concern, but Chris is as blindsided by his own desire not to be reactionary to the casual stereotyping. (One white guest at party of Mike Leigh awkwardness actually hints at a black man’s fabled sexual prowess, while a golf fan claims to be a huge fan of Tiger Woods, as if that absolves him.) Without giving the game away, things turn nasty, and disturbing, and you won’t see the twist coming, I swear. It’s funny and terrifying, and has so much to say, it ought not be this fleet of foot. But it is. Peele treads on toes without tripping up. One of the most original films of the year.

We’ve already seen Elle Fanning in The Beguiled, and although I understand why her willowy presence is so fashionable right now, it’s a dangerous game to appear to be in everything. (I guess when you’re that thin you slot in easily.) She’s in 20th Century Women, a film you’d be certain from its title and its publicity was written and directed by a woman. It’s written and directed by Mike Mills, the one who isn’t in REM and who gave us the memorable Beginners, a film about men, a son and his gay dad. This is, inevitably, more female. Set in 1979 and appealingly soaked in punk and post-punk including Talking Heads, The Damned and The Clash. Fanning is a willowy occasional patron of Annette Bening’s free-for-all hippy boarding house in Santa Monica. Another tenant is Greta Gerwig’s pretentious cancer patient who discovers she has an “incompetent cervix” from her gynaecologist, dances to exorcise her anger, and, we’re told in voiceover, “saw The Man Who Fell to Earth and dyed her hair red.” Bening had her son (Lucas Jade Zumann) late and feels she’s too old to meaningfully steer him to young adulthood, recruiting the other women in her orbit to do it in shifts. So, it’s a coming-of-age, like The Beguiled, except the women are in charge of a teenage boy, not a wounded man. Ironically, he seems old beyond his years, confused that Fanning rejects him since he got “horny”. (“We don’t have sex!” she assures an adult who finds them in bed together.) Billy Crudup, another tenant, also a carpenter who’s renovating the tumbledown hotel California, is too obsessed with wood to find any traction with the kid.

Pregnancy, cancer, menstruation, feminism, all are fit subjects for his ad hoc home-education, and you sort of envy him, as he drowns in radical thinking. I felt that the reliance on narration in the recent Bryan Cranston film Wakefield eventually did for it (it was adapted from a New Yorker short story, much of it word for word). But in 20th Century Women, it suits the quirky, episodic, Wes Anderson-indebted style. When the narration mentions a particular brand of fertility medication, we see a rostrum shot of a single pill from above; when Gerwig talks of a photography project, we see the Polaroids in sequence. That kind of caper. Mills also slots in genuine photos from the period (of Lou Reed, the Sex Pistols, that kind of caper), and it reminded me of the original of The Beguiled, which set its scene with genuine photos of the Civil War. There are no rules against it. I also loved Bening’s line about smoking: “You know, when I started, they weren’t bad for you.” Such economical signposting of age. She says, in narration, that she will die of lung cancer in 1999. It gives you quite a start: she’s suddenly omniscient. Bold writing, and worthy of its Oscar nomination.

In Get Out, Chris is lured into something unpleasant by psychotherapists. In 20th Century Women, everybody is either in therapy, or should be, or offers amateur psychoanalysis at the drop of a hat. If Get Out if post-Girls, this is pre-Girls. Jamie is artistically bullied by Black Flag fans – who spray-can his mother’s VW (“ART FAG”) – because he likes Talking Heads! (“The punk scene is very divisive,” observes Gerwig.) Jamie ends up telling his mom, “I’m dealing with everything right now. You’re dealing with nothing.”)

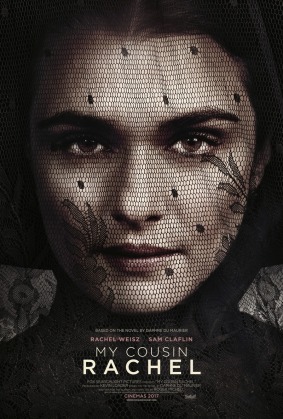

My Cousin Rachel is the second big-screen adaptation of a Daphne Du Maurier novel that’s actually a kind of “reverse Rebecca.” (Why wasn’t that on the posters?) Adapted and directed by Roger Michell, it’s as perfectly poised as The Beguiled, but its dramatic tableaux carry freight, emotional and narrative. Rachel Weisz was kind of born to play the title role, as she is also called Rachel, when Olive de Havilland wasn’t in the 1957 version. Sam Claflin in well cast from the neck up, in that he convinces as the orphaned heir of a wealthy cousin who inherits a Cornish estate and discovers another claimant on his inheritance, the titular cousin, half-Italian and suspected of foul play. When I say Claflin – who takes the role etched by Richard Burton in the 1957 one – is well cast from the neck up, I mean it literally. His face acting is first-rate – although when he has been a gullible fool throughout and finally admits, “I’ve been a fool”, one gentleman in the Curzon quietly exclaimed, “Yes, you have!” and other patrons laughed without malice. But at one point when, as in all costume dramas, he is forced by a sexist orthodoxy to take off his shirt, we see that his shoulders are not shoulder-shaped but triangular, as if perhaps this country fop was a bodybuilder. (In real life, like all young male actors, he presumably feels duty-bound to work out to within an inch of his life, and this often breaks the spell of costume drama. I mean there’s no way Ross Poldark got like that by cutting the grass.)

Look at the above still. It’s a fabulous bit of location scouting in Devon, costume design, lighting, framing and cinematography. They have done Du Maurier proud.

I relish this Catholic spread of cinema. The most generic of all was Berlin Syndrome, a film I took to be German, as it’s set in Berlin, but turns out to be Australian, the third film of Cate Shortland, whose entire output I have seen without trying to. (She also made Somersault, set in Australia, and Lore, also set in Germany.) In it, an Aussie backpacker, Clare (Teresa Palmer) goes back to the flat of a German teacher, Andi (Max Riemelt); they sleep together; he goes off to work the next morning; she finds herself accidentally locked in his apartment. He gets home; she discovers that he has no intention of letting her out. (Imagine the torture of being a globe-trotting Australian traveller being locked into a flat with reinforced, acoustically soundproofed windows so no-one can hear you scream!) This film is a thriller, a chamber piece, and a very effective one. A touch of Rear Window about it, and a bit of hobbling that recalls Misery and The Beguiled.

It’s not deep, but it is lyrically shot by Shortland, showing scenes of “normality” outside the flat that becomes Clare’s cell in slow motion, as if to underline the freedom of ordinary existence. There’s gore and terror, and more than a hint of Stockholm Syndrome – or is it? – to keep the otherwise claustrophobic story going. Andi is well played – he really is charming enough to convince girls back to his flat, and to keep his workmates in the staff room from suspecting (until he starts to unravel) – but it’s Palmer’s triumph. She is the victim, but does not play the victim. You’re willing her to get out.

The tennis is literally just finishing as I finish typing (Jamie Murray and Martina Hinglis are being interviewed after the doubles final). Five worthwhile films, two at the cinema, three at the laptop in coffee shops. If you’ve seen any of them, let me know what you thought.

Love film. Film love.